WE DECIDED TO BYPASS CERRO SECHIN and Chankillo on our way north and save them for our return to Lima. Photos of Cerro Sechin depicted intricate carvings on real rock, not mudstone, and we figured we would see much more at the site. Not.

What we HOPED to see in Cerro Sechin

What we ACTUALLY saw

The rock carvings, about 300 of them, are all you get. But that didn’t diminish Sechin’s impact. While not much is known about the site, the carvings probably date to 1600 BCE. The bas relief art shows axe-wielding warriors, decapitated bodies and mutilated body parts, not exactly where you would take a first date, but they provide some insight into the Casma-Sechin culture.

Carving of a Warrior, Cerro Sechin

Disembowelment, Cerro Sechin

Stone Carvings, Cerro Sechin

Artifacts from Cerro Sechin Museum

The Archaeoastronomical Complex at Chanquillo is about 30-minutes from Sechin on a truly terrible rocky road. It is believed to be the oldest and best preserved astronomical observatory in the Americas, about 2300-years old and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Juan, the park ranger, explained that the site is free and guided us partway into the desert for the best views.

Juan, the Guardian of Chanquillo

Triple-walled Fortress, Archaeoastronomical Complex at Chanquillo

Thirteen Towers that mark the days of the year

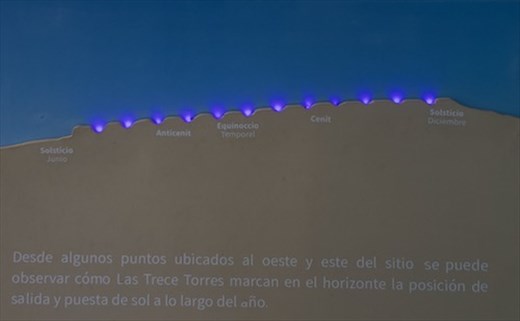

Explanation of how the Archaeoastronomical Complex at Chanquillo works

There are two parts to Chanquillo; The Fortress, a triple-walled hilltop complex and Thirteen Towers spaced along the ridge of a hill. Chanquillo’s thirteen tower had been know for centuries but it wasn’t until 2007 that archeologists figured out their purpose. Looking towards the Towers from the observation point allows one to use the rising and setting sun to mark the solstices and equinoxes and virtually every date throughout the year with an accuracy of a couple of days.

Beware of Mototaxis

After spending the night in Huarmey and several hours of driving through the desert, we happily returned the rental car to Hertz at the Lima Airport. Next time—should there ever be one—we will listen to Carlos’s advice that he would never drive in Peru. Even on the Carretera Panamericana, the Pan-American Highway, you have to be constantly on guard for potholes and high, steep-sided speed bumps locally called rompemuelles, translated as “axle-breakers.” In town you can add mototaxis, hundreds of the noisy, but somehow stealthy, tuk-tuks that follow no rules of the road—or of physics, for that matter.

Roadside Trash, the Scourge of Peru

And while I’m dissing Peru, let me add trash, roadside trash. Tons and tons for mile after mile. I’m not talking about the plastic bottle or sandwich wrapper thrown out to a car window. . .although there are plenty of those. This is household trash, garbage bags full just dumped alongside the road. We will have to think twice—not just about driving in Peru but even returning.