We wake and jostle our belongings together in haste; today, as we have long planned, we will begin our journey into the Dolpa.

Sacks stuffed, teeth brushed, packs on back, we descend the steep

incline of wooden stairs and emerge on the lower deck of our

guesthouse. Gombu, our “English speaking guide” is on the phone. He

hangs up and sighs, starring at the phone like it might change its mind.

Finally, he lifts his head, but not his eyes, and carefully states,

“No porters. No ponies. Not cheap.”

Gombu speaks only in negatives; a style which tends to bump up

roughly with our overly optimistic American angle on language. This is

only one of the many communication challenges that we will encounter

with our local guides; the first, and most glaring, being that Gombu

does not understand English.

“But Gombu, we were told that there would certainly be ponies

available. And that they would be cheap with your contacts. Well,

that’s okay; we’re flexible. So how long do we have to wait? What are

our options?”

To this, Gombu nods his head up and down and says, “Yes.”

When we furrow our brows in confusion, he furrows his.

Then he swings his head from left to right and says, “No.”

And the distinction between speaking and understanding English becomes clear.

Over the course of this adventure, we will come to adore Gombu with

tender, constant and unconditional love. But his “yes” and “no” answers

to our open ended questions will never stop testing our patience and

compassion.

It’s our turn to sigh.

Sangeetha turns to me and says, “I’m convinced that everything that happens is good for us, even this.”

And I respond, “And that is why I chose to travel with you.”

We laugh and surrender ourselves to a situation in which we have no

influence aside from attitude. We retreat to the roof deck where

Sangeetha picks up her drawing pad and I my journal.

“Divots carved in the sandstone walls string together like the

chunky coral strands that the Tibetan women tie around their necks.

Lower teeth jut from caves, which, with squinted eyes, I am surprised

to recognize as stupas: the Buddhist crosses of the Christian world; shaped monuments marking sacred sites. My eyes, adjusted and attuned to stupa

spotting, suddenly spy dozens. But then, when my eyes relax, I realize

that I’ve misidentified a natural pile of rocks for the sacred stupa

shape. Confused, I realize my eyes are lost; confronted with that wall

and question I’ve encountered in the midst of lucid dreaming: But which

part of this is real? And which a symbol? And is this state, of

un-focus, the intention? To blur the line between the sacred and

profane; that one may become the other, not physically by shape

shifting, but rather in the dilation of the witnessing eye? Is this

exercise in the bardo, between the physical and metaphysical,

an unnamed medium of every religion? A task in which we may further

practice, aside from our nightly REM cross training, in preparation for

the navigation our final traverse of life between lives? Is that the

goal of all our sacred symbols? Well if the intention is confusion,

then I am there. Pinching my understanding along with my leg.”

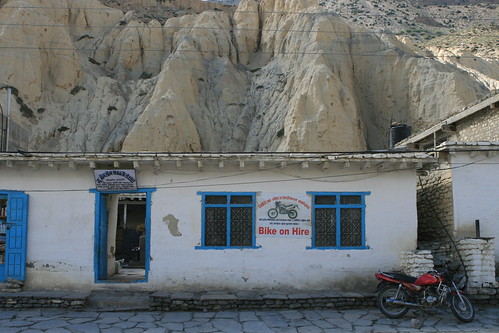

We put our pens down and wander into the streets on a mission. We

have one map of our destination, but figure an additional pictorial

perspective could do no harm. We weave our way through the street

stores, but are consistently spit out of shops, short of our objective:

“No map of Dolpa.” “Sorry. No map.” “We don’t have any.” “Of the Dolpa?

No. Not that.”

Funny that the trail head for the Dolpa hasn’t a single print of its

own mugshot. We’d note it as fair warning, if we weren’t so wrapped up

in the cozy blanket of our own naivety. But at least we got out of that

bed. The preceding day, as our bare-boned bus teetered over beckoning

mountain cliff ledges, Sangeetha and I decided to define the word,

“precarious.”

“likely to fall”

“dependent on chance”

“insecure positioning”

“teetering on trouble”

“bound for natural disaster”

“on the edge”

We take dibs on the things that we will grab should we plummet. She

calls the seat in front of her. I call her. She’s envious of my window.

I remind her of the things that could jut through it as we roll. She

says that if we die, our disappearance might make a great movie. She

claims Carrie Russel. I, Wynona Ryder.

And so, acutely aware of the precarious state of our lives on this

pilgrimage, we are perhaps more accurately labeled stupid than naive.

And there is fear. Great fear, of which we speak little. Sometimes

we poke a little fun and nervously laugh, but we’ve chosen each other

for a serious reason; that in our moments of self-doubt and true fear,

we may ride freely on the other person’s (presumed) faith and (assumed)

sense of security. Afterall, isn’t that the most common function of

couple-dom?

Ironically, or not, that night I have a lucid dream: In the

commotion of typical non-sense, I turn and face a wind and hear myself

say in my head, “I’m dreaming.” My perceptive centers itself. And I

wake up. But into another dream. Where I can hear my voice but am not

speaking. The voice I hear is story telling. It’s speaking of this very

adventure in the Dolpa, but in the past tense. Talking in the future of

a tale all but done. Then the voice becomes my own and I AM the story

teller, speaking with confidence of events long experienced and gone. I

wake up. This time, not into another dream, but into my twisted sheets.

And when I awake, the taste of certainty is still so strong in my

mouth, that I have to shuffle through a timeline of events to convince

myself that I haven’t yet finished this trip.

And only then do I realize the severity of my unspoken fear.

That my subconscious felt it necessary to provide me this favorable

omen means, indeed, a fear was brewing into a less-laughable and quite

formidable threat. It’s as if a third person has joined us, in whose

past tense story of our present tale and in the voice of timeless and

all-knowing perspective, presents a faith upon which we feel confident

placing our bets.

Sangeetha awakes. I tell her my dream. We confess the most formidable of fears. We laugh a little. And sigh more.

We will return. We’ll live to tell our story in the past tense. And to this faith, we suddenly cling.