My friends and I went on a long weekend trip (more like a double date) to Siquijor, Dumaguete, and Twin Lakes last June. It was a much-anticipated vacation--first, since we were raring to go on a break from office work and city life; and second, it was the first opportunity Rina and I would be spending time with Mithi and her beau, Leo.

We decided to veer away from the well-known and frequently visited tourist destinations in the country like Bora, Galera, Sagada, or Palawan; instead we opted to tour places with much the same attractions but where tourists were less likely to be found when we were there. (I guess there was no point in going on a vacation away from the city if the place we were going to felt like we were still in the city, like there was only a change in venue.) Siquijor, we hoped, offered that escape--and it did.

Siquijor, even in my childhood, had been associated with the supernatural. Folklore had made it into a mystical island of magical creatures and the occult. They say it was the land of witches, of the aswang and the tikbalang, and where alot of bad things can happen to you. I guess the belief in these traditional tales kept the older generation (like my parents) from ever wanting to visit the island. After our visit there, I think it was nothing of the sort.

Rather than making you read through a narrative of the trip, let me take you through a commentary of pictures we took instead. Anyway, you can also read much about our trip from Rina's accounts here, here, and here.

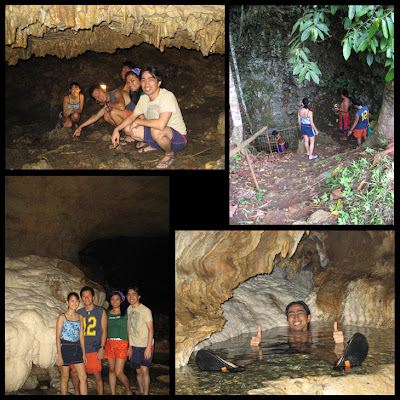

Through Cantabon Cave

What happens when the underlying geology of an area is composed of limestone rock? Yup, you guessed it. Caves form among other natural features. Siqiujor is characterized by karst topography, much like the islands of Cebu, Bohol, Northern Palawan, and other areas where you can find caves and underground drainage.

Cantabon Cave was about a kilometer long. There were a lot of low-lying passageways which almost made us crawl on all fours. The small pools provided a refreshing dip after making your way through mud and muck. Most of the cave formations were still "alive," although it was most unfortunate and depressing seeing vandals and sawed stalactites at some points. Probably some people thought that the cave interior had need for further decorating, or that the crystals found on the stalactites had any value.

Apart from the caving experience, I find the stories of local cave guides interesting too. Unlike the Sagada cave guide who offered me tsongki, our Cantabon guide had told me about their commendable initiatives for managing the caves. According to him, the local caving guides formed a small federation, under the direction of the barangay council, so they can protect the cave and ensure the safety of visitors. They also devised ways on how everyone can benefit from fees that were collected.

It's also fun hearing the creative imagination of various cave guides at work when it comes to describing the cave formations (or their shadows) like the "Holy Family," or the "Bell Shower," or "Susong Dalaga." Local imagination also makes a cave tour unique from the rest. About the kind of wildlife found in the cave, well, I hadn't paid attention to to that story for fear of realizing that I was in the same cave with a huge reticulated python.

Somehow, you'd think, once you've gone on a cave trek, you've been to them all. Not quite. Of course, once you're inside a cave, it's no different from other caves: it's dark (obviously) and you'll see the same stalactites and stalagmites. While each cave will vary in orientation, length, and formations, you can always count on your own experience to be unique. My experiences of going through Sumaguing Cave in Sagada and in Langon-Gobingob Caves in Samar were very different. The people you go with definitely play a huge factor in your caving experience; needless to say, it's always more fun going with people you enjoy hanging out with.

Jumping off Cambugahay Falls

Like all the waterfalls I get to visit, it's imperative that I jump from the falls. Well, maybe not all (thinking of Maria Cristina Falls in Lanao). I don't know when this fascination for jumping off waterfalls ever came to me... maybe it was in 2003 after going to Gabaldon and jumping off an 18-foot boulder along a river, which was of the almost same depth.

Cambugahay Falls offered a series of waterfalls which cascaded one after the other. We went falls-hopping: swimming and jumping off the waterfalls until we got tired and decided to head to the next falls. Each of us wanted to have our pictures taken while momentously jumping off a waterfall, caught suspended in mid-air. If my friends found jumping the first time difficult enough, it was more difficult getting to do it several times so your picture could be taken perfectly.

Local residents took to the falls to have picnics or have huge family outings. Kids waded and swam from the shallow parts of the pools while teenage boys were more fond of doing impossible somersaults from the waterfalls. When my friends and I arrived, it was obvious to the locals that we came not from town. (I wonder how local residents ever get to notice that.) It was nice feeling that locals welcomed visitors like us. They even cheered while we were doing the jumps. A manong, whose entire family was having a picnic from across the pool where we were sitting, even offered me a shot of the liquor they brought, which was probably a locally-made wine called tuba. I politely declined for fear of losing my wits while swimming. When we were on our way to leave, the same manong smiling, called to us and waved his hand in farewell. I waved back as a sign of my gratitude for their hospitality, while my mind was half-hoping that I can come back someday.

Kayaking at Coral Cay Resort

We opted to stay at Coral Cay Resort, which was situated by the beach. We figured it was the best way we could enjoy unlimited access to the beach without paying extra for entrance fees or transport. It also had a small pool which allowed us to go swimming even at night. It might not be the ideal place for snorkeling (or diving) since there were more seagrass beds than fascinating coral gardens. But what they lacked in natural tourist attractions, they compensated through other amenities like a small gym, a swimming pool, and kayaks!

I never thought kayaking on open water could be so much fun! It was a good way to exercise my arms and practice paddling. Making precise turns and stops weren't as easy as I thought; racing was much easier since you only needed to paddle harder and faster.

The resort had built a small bamboo raft with a mini roof for shade against the sun, and anchored it about several hundred feet from the shore. It was to serve as our "base of operations" while we went around practising our kayaking maneuvers, or snorkeling to see what marine lifeforms were present. In between strenuous activities we just lay down on the raft to get our skin scorched by the afternoon sun. The only thing missing was food.

Around Siquijor

We chartered a multicab (a smaller version of the jeepney) to take us around the island. It was easier and more convenient than having to commute from one place to another.

After visiting the Cantabon caves, we headed for Mt. Bandila-an which was yet another tourist attraction. The small mountain was roughly 600 meters high. Roads were constructed to cut across the mountain and make it accessible. So when we got down from the vehicle, the trek to the peak was only a few hundred paces away. A lookout platform was erected at the peak to enable tourists to get a 360 degree view of the entire island. (Well, except at some angles where the foliage became too high or dense enough for anyone to see through.)

Mt. Bandila-an, although probably not that much of a come-on to hardcore mountaineers, is an attraction for birders. According to Haribon-BirdLife's Philippine bird directory, four subspecies of birds can only be found in Siquijor and nowhere else in the world. Unfortunately, their status is far from secure. We hadn't come prepared with our binoculars or Kennedy's Philippine bird field guide so there wasn't any point to birdwatching right there and then. Besides, it was almost noon and birds were hardly active at those times.

The place looks like a perfect hang out especially for teenagers and couples who go out on dates or those wanting a little bit of "you and me." Maybe the reason why three crucifixes were erected at the base of the lookout was to keep visitors from doing any mischief or getting any naughty ideas; or maybe, the crosses were actually put there for people who went on pilgrimages or prayer walks.

Speaking of sacred sites, we passed by the old historical church and convent of St. Isidore Labradore in the town of Lazi, which was built in 1857 and completed in 1884. Siquijor, as you know, is an old Spanish town and boasts of several centuries-old infrastructure. Unlike the Gothic architecture that characterizes much of the church architecture in Europe, the church and convent of St. Isidore Labradore is devoid of intricate designs. The base structure and walls are made entirely of stone, where moss and ferns have thrived after years of being white-washed and beaten by the elements. Windows made of wood and capiz shells even remind you of scenes that you've read in Rizal's Noli or El Fili.

One surprising observation I had was the presence of an existing road network throughout the whole island. These were even well-maintained and made most of the island readily accessible. We were traveling across the interior towns of the island and yet roads--whether these were concrete, asphalt, or a pulverized mixture of gravel, sand, and asphalt--were still present, which was unlike the towns in the provinces of Quezon, Samar, or Mindoro. Even electrification was available! Houses located even in interior towns were mostly built of concrete and processed wood; seldom would you see houses made of nipa.

I thought: Siquijor was established as a parish by the Spaniards in 1783 while Polillo in Quezon--a town closer to Manila--was established even two full centuries earlier. Yet, it seemed that in my travels to these two islands, Siquijor had progressed more in terms of infrastructure development. In Polillo, to get to the adjacent town, you had to experience two grueling hours of rough dirt road, which became almost inaccessible when the rains poured.

How come other towns in the country were not as developed as Siquijor? Maybe Siquijor had more access to funds since it became a province in 1971, while other towns remained municipalities. Or maybe its historical attachment or geographical proximity to the province of Negros, which became rich owing to its vast sugar-producing plantations, made it as much a recipient of needed infrastructure? Government leadership in Siquijor, I concluded, may have been the key to their progress. I think their leaders carried out projects and programs much-needed by their constituents. I mean, roads are essential for trade and tourism. It's vital for development. With roads, transporting agricultural produce from farms to the market can be done in a shorter span of time. Tourism can flourish since natural attractions become accessible to more people. If tourism and trade thrives, wouldn't that create revenue that the entire populace can benefit from? How come other government town leaders don't see this simple importance?

A Brief Side Trip to Twin Lakes, Negros Oriental

After Siquijor, Rina and I made a side trip to Twin Lakes in Sibulan, Negros Oriental, which was roughly an hour-and-a-half away from Dumaguete. The Twin Lakes is made up by Lake Balinsasayao and Lake Danao, which is separated by a narrow mountain ridge. You can hire a habal-habal (or motorbike) somewhere along the highway in Sibulan, which can take you straight up to the entrance of Twin Lakes; thus, saving you the time and effort of having to hike your way up through undulating terrain, which can be quite a distance and physically challenging for some people. Unfortunately for us, the motorbike failed a little beyond halfway, and we were left with no other option but to trek the remainder of the way.

A three-storey lookout was built along the ridge separating the two lakes. From that vantage point, you can see both lakes and the dense pristine forests that still cloaked the mountainsides. Our pictures could've been better, I thought, if not for the rain since the sky would have been bluer and the daylight could accentuate the lush green vegetation and the blue-greenish waters. From the main entrance though, you'd have to trek about half a kilometer to get to the lookout. Pathways made of stone blocks were constructed along the perimeter of the lake leading to the lookout.

On our way out, we encountered a group of birders--an unmistakable bunch especially when you see the binoculars that hang around their necks, or their cameras with huge, long telephoto lenses, and spotting scopes. One of them asked us if we happened to see (or hear) the Tarictic Hornbill, to which we responded that we didn't and then continued to walk our way out. (It was quite an amazing, if not surprising, encounter because not all Filipino tourists you meet ask the same unexpected question. And they fortuitously happened to ask two former Haribon employees? What were the odds indeed.) Well, Twin Lakes (or Cuernos de Negros) happens to be a haven for birdwatchers as well; it's listed as an Important Bird Area in Haribon-BirdLife's directory.

To sum it up, visiting Siquijor and Twin Lakes was quite a journey. If you're looking for a place away from the commonplace vacation areas to reflect, or just spend a good time sight-seeing, trekking, boating, or even birdwatching or fishing, or become really adventurous, I'd recommend going to these places.