On Monday, we did the usual Monday thing of working on kanji before meeting with the high schoolers. We also got back the results of our first kanji test. I was not too happy with the points that I missed.

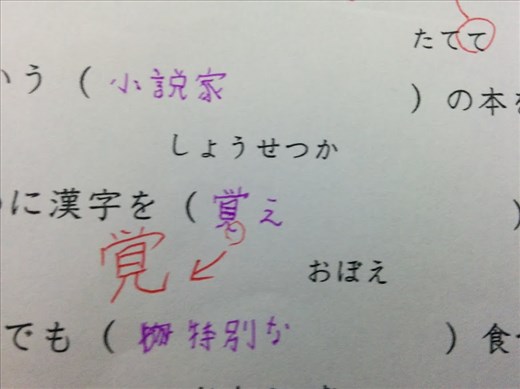

It’s going to be hard for anyone who hasn’t studied Japanese to be able to give a fully educated view on this, but do you see that much of a difference between the kanjiI wrote and the correct kanji? That difference was worth half a point. I missed another half point on the reading section when I didn’t know what a certain kanji was so I made an educated, but completely wrong, guess.

Elsewhere on the test, I missed a solid point because one of the lines on one of my kanji didn’t extend as long as it should. I also missed one point because I read “han” as “hon” and ended up writing “really” when the word I should have been writing was “peninsula.”

Now, I have no problem with missing points on the test. I deserved to miss points. Especially, I deserved to miss a lot of points for not realizing that I was writing the wrong word. Because that’s a huge mistake. Having a single line in a nine-stroke kanji that doesn’t extend as far as it should is not that major. But, for Yamaguchi-sensei, those two mistakes are equal. I’m not sure how.

During the meeting with the high schoolers, we were responsible for presenting the introductions which we’d written the week before and memorized over the weekend. We had memorized them over the weekend, right? Not for the first time, I found myself thanking my Carthage professors for things I’d quietly cursed them for in the past. I might not have enjoyed memorizing speeches for Japanese, but I’d had to do that enough times that I couldn’t help but become good at it. So yes. I had memorized that script over the weekend, and was prepared to introduce Ai, favorite book at all, without even needing a note card.

We were split into three groups, told to introduce our partners to the rest of the group, and then vote on the best presenter. The best presenter from each group would go up and give their speech to the entire class. There were prizes involved, but this was not mentioned until they were being given away. And, as I commented softly to Dan as we went down to meet the high schoolers “so what she’s saying is that if we do badly during our small groups, we have less work to do?”

Certainly, that was was the theory everyone in my group seemed to subscribe to. All of our presentations were kind of lackluster and tired, and when it came time to vote for our representative at the end, there was silence for a while. Finally, Indu said “Ai’s presentation was pretty good,” and we all kind of nodded, so Ai ended up being the victim who needed to give the presentation in front of everyone. And the rest of us could sit back and watch. That was worth more than an Osaka Gakuin beach towel, which was what the prize for being chosen as the best presenter in the small groups was.

Class was over, and I hung around my apartment and walked by the river for a while before “meeting up” with people to go get ramen. Getting ramen was a whole group activity, and the group was scheduled to meet at a certain train station at 19:00, but for those who didn’t know how to get there, we could meet at Shojyaku, the train station nearest my apartment, at 18:40. At 18:20, Umi showed up in my room, asked if I was going to get ramen, and told me “not yet, soon,” when I stood up. At 18:30, I started hanging around outside her room. At 18:45, she finally came out, and off we went.

At the train station, we ended up semi-coincidentally arriving at the same time as two Japanese students, one of whom was also going to get ramen. So we got on the train and rode together a number of stops. No one was talking that much, so I pulled out my tablet and continued working on a personal statement for an REU. Taka asked me what I was doing, so I explained that I was writing an essay for an application for mathematical research.

“What kind of math?”

I don’t like that question too much when it’s asked by a non-math major, even in English, because most of the time the reaction to your answer will be “I don’t know what that is.” Attempts to simplify the description won’t help if they don’t have the background to know the different branches of mathematics. But it’s rude not to answer, so I just smiled and said “graph theory?”

“Graph theory? Sounds difficult.”

“No, it’s not.” And, to prove it, I opened a new document and started drawing some simple graphs. And, again, I didn’t have any of the right terminology, so I was just calling everything by its English name and hoping that worked. The results were mixed. They seemed to understand what kind of structures graphs were, but they still thought they were incredibly complicated and difficult. No matter how many times I tried to explain it’s simple, they didn't believe me.

And that’s when I knew I had to work harder to study Japanese. Because if I can’t even explain the basics of graph theory during a twenty-minute train ride, what can I do?

We met up with the other CET students and headed to some mysterious place to get ramen. I ended up sitting with John, Molly, and Jin, so two students in a higher level of Japanese than me and one Japanese student. We talked about a lot of things, including math (Molly had been considering a math major or minor when she’d started at college. Then she’d taken a math course and decided against it) and the courses and things we needed to do when we got back to our home universities. Dinner was pretty leisurely, and by the time I got back to my room it was 21:30 and I hadn’t even looked at my homework. One of these days I’ll learn...