Singapore is many things, though few of them as described by

friends before I arrived there last week. Mostly it is lush and green, and the

trees in the carefully tended parks are heavy with staghorns and epiphytes.

Orchids grow in roadside plantings, and everywhere there is the heavy smell of

the tropics.

The city is clean, and well organised in a bustling sort of

way. The streets are full, but not chaotic, and the markets crowded with

hawkers selling tropical fruit, clothes, mobile phones, and miracle cures for

baldness and skin disorders.

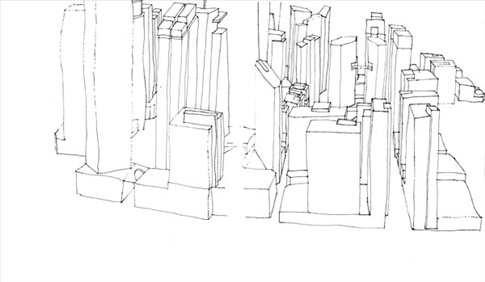

It is also the city of the future, or rather futures,

because the different versions of this event compete and intertwine. The oldest

of them are the brightly coloured tower blocks with ground level food halls and

wide marble courtyards. The newest are the glass and steel towers of the

business district, clustered spiky in a single block overlooking the river.

Neither has the colonial era disappeared. Neoclassical churches

mix with colonnaded public buildings. All around is the distinctive Malay

architecture that borrows everything from Moorish arches to Corinthian

capitals. There are mosques and temples for every order, single story shops and

gigantic malls.

And then there are the futures to come. Bright arcologies,

buildings punctured by light and ribbed with walkways and gardens. Some are

being built, others only wood and plastic models that cover the floor of the

gallery of the Urban Redevelopment

Authority.

The poet Alvin

Pang described the diorama, at once infinitely speculative and reassuringly

concrete, as perhaps the city-states true artistic expression. It is certainly

remarkable. Crowds of students and tourists come to see it, and observe the

shapes of a city that is outside obscured by heat, rain, traffic and the

necessities of the material world.