Old, or rather historic, or rather Fatimid, or rather

Islamic Cairo has changed its name almost as often as rulers have come and gone

over the centuries. The most recent of the names [old and historic] are

designed to reduce the emphasis on precisely what makes this part of the city

so endlessly fascinating – its rich heritage of Islamic art and architecture.

For the past week I have wandered its lanes and alleys.

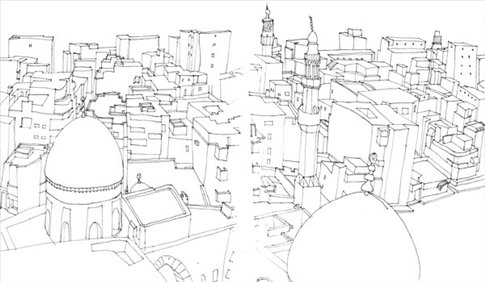

Everywhere there is a jumble of modern apartments, Ottoman villas, and Mamluk

and Fatimid domes. Because Cairo is a living city there is no limit to the

intermingling. Windows are cut into the walls of a 9th Century

fortress. The arched façade of a hospital remains, but not its once domed roof.

A Turkish barrack, taken over by the British during their time here, lies

abandoned, mortar crumbling down sandstone walls.

From the roofs of buildings, or indeed any high place, the

city stretches out in greys and browns. The horizon is not visible – dust and

pollution put paid to that - but minarets and domes push up between habitations

and steadily recede into the distance.

The best of all the high places is the minaret of the mosque

of Ibn Tulun. One of the oldest, and certainly the largest mosque in Cairo, its

architecture is unique in the region. Its closest cousin is the Great Mosque of

Samarra, Iraq on which it was based. The minaret has an external spiral

staircase, and from the top there is no end to the dizzying views over old and

new quarters of the city.

At the eastern end of the mosque

is the Beit al-Kritliyya, or 'House of the Cretan Woman', now the Gayer-Anderson Museum

after its final resident, a retired Major and collector of Asian and Middle

Eastern art and artefacts. The second floor of its central hall is ringed with

wooden screens, and from here the women of the household looked down on

intrigues and plots in the room below.