A Caribbean scene on a New Zealand sandbar: a straw hat topper on a green folding chair, a cooler to the left with a box of wine balanced on top. A man’s bare feet stretch out onto the sand, waves lapping at bony toes. Under the sunhat I’m surprised to see the beard of a Maine lumberjack in the dead of winter, dark & thickly-grown. He turns to us, sprawled on our quick-dry towels, slurping up sunshine like gluttonous lizards.

“Where are you girls from?”

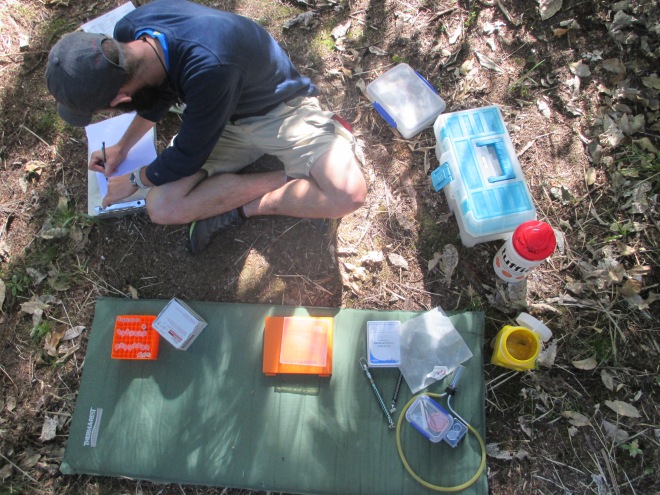

An American accent, but clearly not a tourist or backpacker. Over a few hours and a few sandy glasses of box wine (a delightful treat after two long days of hiking), we befriended Chris Niebuhr, a Texan who gave the finger to American life in favor of Caribbean beaches, then moved on to New Zealand to study birds. A PhD student at a university in Dunedin, Chris is a man of many titles: resident sand bar king, generous gifter of box wine to lowly pack-bearing hikers, wildlife zoologist, studier of avian malaria (much like human malaria, I learned, but not transmittable to humans). Chris’ “office” is a cozy jungle clearing behind the Bark Bay Hut in Abel Tasman National Park, surrounded by delicate, billowing, black netting used to catch unsuspecting birds. His tools are spread on a Thermarest pad on the ground: vials of bird blood in neat rows in a plastic box, a heavy metal clip board, and “The Hand Guide to the Birds of New Zealand,” a thrilling read, to be sure. There’s something mysterious, museum-like about his scientific tools alongside his camp stove and light-weight hammock, giving a sense of impending discovery.

Chris spends several weeks of the summer at Bark Bay, catching, bleeding, tagging and releasing various song birds. The price he pays for these glorious summers of field work is winters holed up in a lab, testing his samples for disease, namely avian malaria brought over by the bastard, non-native, colonial English birds, who can be symptomless carriers. While we didn’t get to see Chris sciencing with a bird, we did spend an evening bleeding him of bird information, learning about the multitude of creatures traipsing around us on the sandbar that evening: oyster catchers digging in the sand with long, carrot-orange beaks, snake-necked shags airing their bat-like wings before flight (which they have to do because they are deep divers and don’t have the glands that help other birds dry quickly...). An interesting person in an interesting place.

Can you spot the netting?