Day 9 – Drive to Tsetserleg

Tsetserleg is a “real city” with electricity, Internet, running water and pavement. Our ger had electric lighting (well, ok AN electric light), and we got to charge our cameras and ipods. We missed on the Internet, mostly because we were too tired to walk back into the center of town. We did get showers, the third in 9 days, again at the public shared shower.

And we had our first honest to god water-flushing toilet since leaving UB 9 days before. This was at the cafe where we had an early dinner/late lunch. The running water ran out somewhere before or after the asphalt, but both fell short of our accomodation.

When we first pulled up to the cafe, it was about 3 in the afternoon. Every building in Mongolia is an anonymous box, sometimes bearing a cyrillic sign, and very occasionally a picture or something legible to the roman-alphabet-only club members. Now in 9 days of driving you do a lot of stopping. Often for bio-breaks, but also the occasional flat tire, photo op, or what not. The Mongolian steppe is beautiful, but anonymous. Frequently, the purpose of our stop is not immediately evident – there might be a special overlook just behind a rock, or a monastery tucked around a corner, or whatever. So it is that every time the bus comes to a halt, the car fills with a familiar chorus. “Toilet?”, “Flat Tire?”, “Photo?” as everyone takes their guess. Then Doc will nod the affirmative as he repeats back “Toilet” or whatever. But we were all befuddled by this one. We had made a few stops in the city – for fuel or groceries (“Shop?”). But the shops all had big signs with faded photos of veggies and fruit (which they don't actually stock, but I suppose there are no truth in advertising laws out here). And so we all sat in silence as we waited for Doc to declare the purpose of our stop (or to jump out and do something). The moment dragged on. Finally, Doc said “No?” as he looked around at all of his unmoving passengers. “What is it?” was the chorused reply. “Lunch!” “Ohhhh!” and we all excitedly poured out of the van.

Besides hamburgers, real fresh veggies, and lasagna there was nothing to report on from Tsetserleg. It was less depressing than crap-town, to be sure. With some vestiges of an actual economy, including at least one factory doing something. But the desert had long since reclaimed most of the roads, the manhole covers from what sewerage there was just sort of stuck up out of the hard dirt in random places. Like everywhere in Mongolia, the permanent structures were bleak soviet-era concrete block buildings, ugly when new. Most of the large, industrial buildings were living answers to the question – 'what happens to steel and concrete when you abandon it in the harshest imaginable environment for a few decades?'

Day 10 – Drive to White Lake

Tanks full – of petrol, fresh(er) food, and ipod-juice we trucked out for our final scenic destination of the trip “White Lake”.

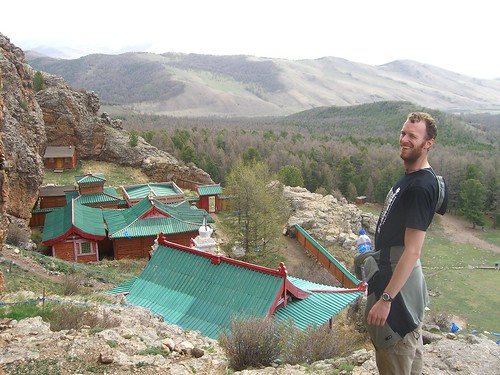

En route we stopped at a restored Monastery.

Basically destroyed under the Soviet-puppet rule, it has been lovingly restored. There are not very many old permanent structures in this country, and the few historic monasteries they have are all significant both historically and religiously. Most religiously significant spots are identified by a piling of rocks and accumulated offerings, usually strung with blue prayer flags. To a nomadic people who in ancient time regarded the great blue sky as the source of divine power, these were the only practical structures to constuct, but also all that was appropriate. It would be counter productive to block out the sky.

But with the arrival of Buddism beliefs merged and adapted, and a few monasteries were built.

The setting was beautiful, as the monastery was established on a natural granite tor sticking up out of the otherwise rolling hills in an alpine area like the sharp, hard bone of a compound fracture jutting out of soft flesh.

I wondered whether the natural geologic parallels to the man-made tor was a deliberate symbolic aspect of the choice, or if the site was selected merely for it's inherent specialness.

Visiting it required some significant use of the quadracepts, and also the inner ear. One area was only accessible via a vertical rock climb, a short distance up, but perched atop a very preciptous cliff. There was no protection, but the rock was quite rough and provided easy hand-holds. Still, any spill would definitly prove lethal.

The drive was only a few hours, but almost entirely uphill. At the “waterfall” we were at alpine altitude, but had decended back into steppe at Tsetserleg. For “white lake” we would climb higher still, to air thin enough that we could feel it. White Lake is a Volcanic lake, inside a huge caldera. It eventually drains northwards, through rivers and lakes to Lake Baikal, in Russia, and on to the Artic Ocean.

The area around the lake has two characters. Immediately adjacent, and in the same depression that the lake itself inhabits, time and weather have worn rock into soil, and smoothed the rough edges. Erosion has carved some spaces back from the water's edge where hillsides can shelter from the biting wind. The lake is wide, but not so wide you can't see across it – a kayak could cross in an hour or so. The length was more significant, and though we could see the far end we would not attempt to reach it by foot, hoof nor wheel. A few dozen miles, I would guess, and upwind. The next two nights we would camp in gers by the lake.

But before we reached our camp we drove through the “other” part of the White Lake area. Extremely rough, and covered with razor-sharp volcanic debris, this area was old enough to have mature pine trees, but was geologically very new. Here was the more recent activity, and we climed up the side of a steep “hill” to see the caldera. This one was much smaller, about a hundred yards across. Had it not been for the thin air we could have climbed down to the bottom, but the sides were steep and the sand loose, and we were sucking wind hiking at altitude. On the way back down we noticed a few smaller depressions where vents must have poked through, spewing ash and chunks of rock. The side of the mountain was very steep, and the earth only loosely held by scrub and trees, yet this little caldera, no deeper than I am tall, was still unfilled. I don't know how long these things take, but the impression of newness was reenforced by the areas of charred tree trunks not far away.

There were four gers at the campsite, and one permanent building; a small two story house made of wood. The lower floor was a bedroom, little bigger than the roughly queen-sized bed it contained. Above this was a combination living room, kitchen, second bedroom where the family spent the whole day when not outside working. The gers were strictly for tourist guests. There was also a proper outhouse with two sit-down loos and actual doors. This was made entirely of wood, and had no running water. It also had a sort of vent out the side for the vault below, and when the wind came from a certain direction there was a rather swift updraft in “the critical places”. Even so, it was pure luxury after almost two weeks of strained knees unused to squatting. It was also only for the guests. The family used a facility that was also on the edge of the compound at a discrete distance. I didn't bother to examine it closely, having seen it's brethren many a time. From a distance there is just three sides of canvas held up by four stakes in the ground. The vault is covered by wooden planks, with one plank deliberately missing from the middle. Both faciliites were sort of mobile, with no foundation. When the time comes a new pit is dug, the wooden structure is dragged into place, the old pit is filled and the location marked with stones or old tires or some other sufficiently semi-permanent designator.

We were right on the edge of the lake, and could look out from our ger door across the water to the far side and mountains behind. It was dazzling in bright sun, the sun still high past dinnertime.

Again here, we had two nights.