The Blue Mosque is named for the tiles, imported from

Istanbul during the days of Ottoman rule, that decorate its interior walls.

Every surface is covered with flowers and floral motifs and the simple but

elegant exterior contrasts markedly with the baroque patternings inside.

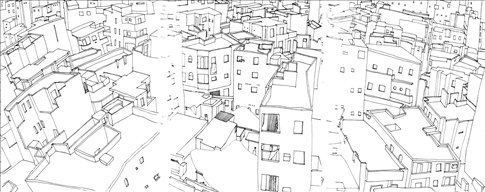

But my interest is above, in the view from the single

minaret with its curled and coiled internal staircase that rises through

patches of light and dark to a point far above the rooflines of the

neighbouring houses. From here you can see south to the Citadel and Sultan

Hasan, east to the city of the dead and Muqqatam, north to Bab Zuweila, west to

the high-rise of downtown and sometimes, on a very clear day, the three bright

shapes of the pyramids at Giza.

The surrounding district, the Darb al Ahmar, is currently

being restored and redeveloped by the Aga Khan Development Network. While rich

in monuments the district is also one of Cairo's poorest. Efforts to improve

sanitation, repair crumbling apartments and provide employment and training

have gone hand in hand with the larger work of restoring historic mosques,

shrines, palaces and madrasas.

Dina Bakhoum, programme manager for the

district, tells me that the Blue Mosque will take three years to stabilise and

restore. Time enough to repair the damages of the last six centuries, and to

remove the steel and wood buttressing that supports the arches that divide the

open courtyard from the building's interior.

From up above the street noise fades.

Competing sounds – children playing, the buzz of a band saw, the honk of taxis

and sharper beeps of motorcycles, the rattle of gas cylinders on cobbled

surfaces – are carried on the shifting wind. I look out over a landscape old

and new, beautiful and forgotten, sacred and profane. I lift my pen, and draw.