Day 5

The next morning we came down for

breakfast and noticed the fruit was peeled. Actually, I really

noticed this when breakfast was brought for another table in the

restaurant and their fruit wasn't. I never said anything, but they

had noticed my peeling my fruit the day before. Awesome.

We were off for the Art School. As a

part of the active effort to preserve the culture, all the

traditional crafts are supported by a training program here;

carpentry, embroidery, metal working, painting, and doll making.

We also went through the Folk Heritage

museum, which had an example of a traditional Bhutanese home,

complete with artifacts of daily life. It was groovy, but our mojo

got a little messed up by a tour of Chinese “VIPs” (and it would

seem their wives, cousins, next door neighbors etc.) who not only

ignored the “no picture” signs but also happily bypassed the

little ropes and “no touching” signs to pose in the display

holding the various kitchen/farm/religious implements. Like a German

in a uniform, a Chinese bureaucrat with a “VIP” card is an object

to fear and loathe.

One cool thing about the Bhutanese

homes. They all have a prayer room, a space set apart with a small

shrine. This room usually has nothing but an altar and cushions, and

one chair. The chair is not, however, for the patriarch or any

member of the family. The chair (really a raised dais with a cushion

for sitting in the lotus position) is reserved for monks of a certain

level. At special occasions a monk will visit the family to perform

rituals. Most of the time the monk will sit on a cushion to the side

of this chair (and the family on the floor). However, on very, very

special occasions (a few times in each lifetime for most people) a

more senior monk will be in attendance as well, and occupy the chair.

So nearly every home has a piece of furniture that by tradition gets

used only every few years. And it's not like a box of Christmas

decorations that are stuffed in the garage or the attic for 11 months

of the year – the prayer room is used frequently by the family

(perhaps several times a day by a pious family) but the chair will

always be left vacant.

We were quick through both of the Folk

Heritage Museum and Art School, as we also needed to get over to the

city of Punakha. The road takes us up over a very high pass (4500

meters or so – basically the top of Mount Whitney) and back down,

also through another checkpoint.

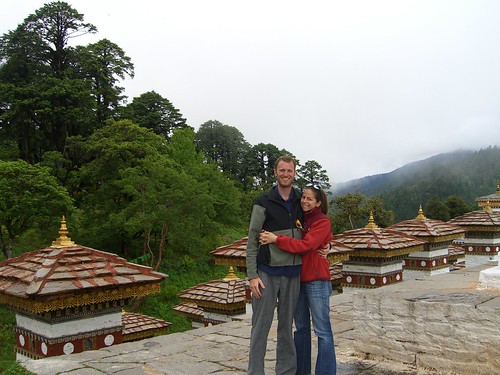

En route is a big new temple, one

even Tashi hasn't been in yet it is so new, and a place where the

former queen built 108 stupas to protect the King and the army after

their campaign against Nepalese insurgents.

We were in the new temple for about

three minutes before getting shooed out – some VIPs were on their

way to see it.

Technically, this is a family temple of the royal

family, and so when a prince, queen, or other royal wants to use it

it is closed to the public. Too bad, it's a very cool place. New,

and with many modern elements, like realistic faces on many of the

paintings, but still very much fitting to the traditonal aesthetic

and clearly a Bhutanese temple. Along the top of the walls in the

main chamber are murals dipicting the history of the Kings of Bhutan.

Outside (where we could still spend a few minutes) angels flew with

faces of Bhutanese children.

As we made our way back down the other

side of the pass we quickly pulled to the side of the road for a

motorcade heading uphill – the Prime Minister and two queens (the

King has four wives). Phubu quickly pulled off his hat, and he and

Tashi both bent their heads to look down as they drove past. So, I

guess that was the VIP. A couple of days earlier we had pulled left

(slow lane – they drive on the left here) and let a big SUV pass

us. Then too Phubu had quickly taken off his hat. It was a prince

driving himself (you can tell by the license plate).

Sadly the weather at the pass was foul

and we didn't get the vista of giant himalyan peaks in the distance.

We tried to wait it out and eat near the peak, but no dice, instead a

mix of rain and snow. In eight days this was pretty much the only

time the weather caused us any real trouble – despite what is

supposedly the “wet season”.

The climate and flora on this side of

the pass is very different, on account of the lower altitude (only

1200 meters or so). They call it “semi tropical”. I don't know

about that, but it was hot.

After lunch our next stop was “The

Temple of the Divine Madman”. They love this guy here. There

are all sorts of wild stories about him – apparently when he wasn't

battling demons he was drinking and chasing skirts. Among the

stories of debauchery are tales that he bedded his own mother. But

whatever, I guess battling demons gets you lots of credit, cause he

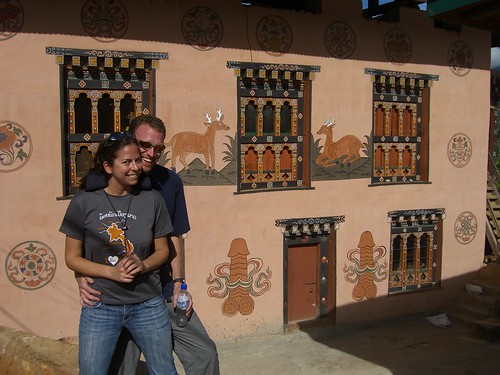

is a HUGE deal. Especially in this region. Apparently he figured

out that evil spirits are scared off by his... well you know. So

people will buy a wooden... and hang it under the rafters of their

houses. But for some folks, just in case, they seem to augment this

by painting phalluses on the outside of their homes (which double as

fetility charms). Susan just loved this, and would have filled an

entire roll of film with photos of this if I had let her.

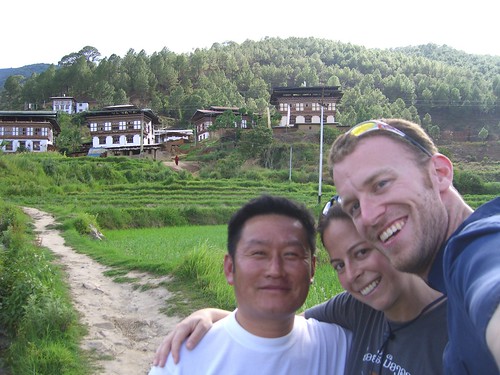

The giant wooden phalluses continued

after we got to the temple. As Tashi explained on the walk through

the rice fields that surround the temple, people come here if they

are having trouble conceiving. A special offering and a special

blessing from the resident monk and many people find success. Susan

asked if there was a reverse charm, maybe one that provided a couple

of years protection?

This got us into a discussion of sexual

politic, comparing American and Bhutanese ways. Tashi was surprised

to learn we weren't married, and really surprised to learn that we've

only known each other since November. I hadn't realized he'd missed

this, but sometimes things get lost in translation.

Anyway, Bhutanese often practice

polygamy, though it is slowly losing favor. Interestingly, this is

not only men with many wives, but some wives with many husbands.

Typically, the multiple spouses are siblings. The King, for example,

has four wives, all sisters. But even a farmer's daughter might

marry four brothers. The reason for this is to preserve the wealth

and property. While not a hard and fast rule, husbands typically

move into the homes and farms of their new wives. For a wealthy

landowner, dividing his land among several offspring is not such a

big deal, but for those with a more marginal bequeathment polygamy

lets them keep the parcel intact for another generation. One

daughter with four husbands means a single parcel, worked by four

able-bodied men. Four daughters with one husband yields the same

result (although multiplying the challenge for the grandkid

generation). This practice is slowly being discouraged as Bhutan

tries to modernize certain ways. A minister once challenged the King

if he thought he was setting a good example with his four wives. His

retort was that any young men should just look to him to see a great

example of why not to.

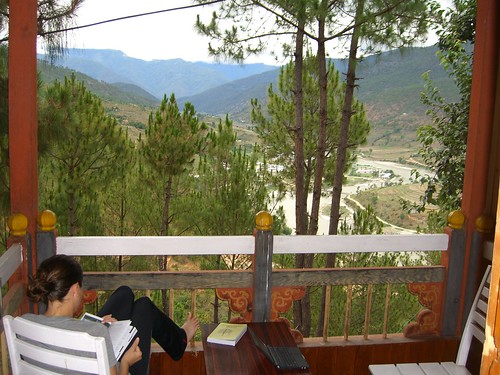

The walk through the rice paddies was

beautiful and bucolic, with folks cutting weeds and planting rice by

hand. Our hotel sat high on a hillside overlooking Punakha.

We had

a nice little balcony, where I wrote for a few hours and we watched

the sunset. The whole country is like a million postcards stiched

together.