The moon crossed the sky, coyotes howled in

the distance, and the campfire crackled, yet my focus centered on our

instructor and guide, Ernesto Molina Villalobos, as he recited ancient tribal

myths counterbalanced by tales of modern-day political struggles facing his

people: the Seri Indians of Sonora, Mexico.

The Seri’s ancestral homeland is Isla Tiburon (Shark Island) a six

hundred square mile island adorning Mexico’s Sea of Cortez. Today only six

Mexican military personnel occupy the island on a regular basis. For one week,

this island would be our classroom.

I was on Isla Tiburon to learn through practice

the ancestral skills of the Seri. Relentless curiosity and unanswered questions

about traditional cultures drove me to enroll in a course offering an immersion

experience focused on traditional native skills. I found such a course, through

the Boulder Outdoor Survival School (BOSS).

Traditionally, the Seris were nomadic hunter-gatherers who depended on the sea for much of their livelihood. Today, they are settled on reservations in Sonora, Mexico. Their population is about 500, with only about 200 of these being sangre puro (pure blood) Seris. Few practice the old ways, though knowledgeable elders remain.

How can traditional lifestyles and skills

endure in a technologically advancing world? What is it like to live in harmony

with the natural environment? What was life like here thousands of years ago?

Is there hope for contemporary nomadic cultures?

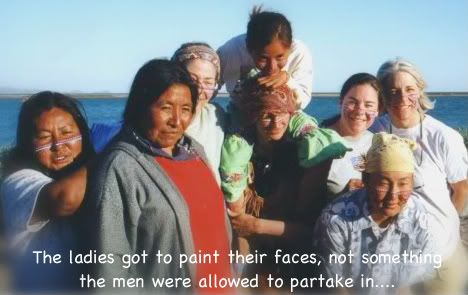

Answers surfaced over the week as our group

distilled fresh water from saltwater, dug for clams, made fish spears and then

obtained meals by successfully using them, built traditional Seri shelters out

of ocotillo cactus, gathered roots to make dye for baskets, and started fire by

friction with gathered wood. Answers also came from chance events.

Such as the day we discovered that one of the

Seri children in close contact with us had lice. As traditional would have it,

the natural remedy and preventative measure to keep oneself louse-free is wild

tobacco, so we gathered wild tobacco, boiled it to a tea-like broth and then

soaked our hair in the concoction. No one departed the island with lice.

After a week on the island, our group visited

the Seri Museum in Bahia Kino. Moving from diorama to diorama, I realized—I can

make that; I know how to use that object; this artifact is poorly crafted and

that one is amazing. Something in me had shifted during my time on the island.

I could look around the museum and understand the displays in a new way.

I felt a deep connection to the past and it

wasn’t abstract or theoretical as it had been so many other times in so many

other museums. It was real, practical and concrete.

I thought to myself, to comprehend the Seri’s

perspective your mind must open to a completely new reality and allow that

there are other ways of being, living, and relating. Abandon your comfort zone.

Adopt the traditional Seri ways for a while and discover a foreign land within

a foreign land. Discover the Seri world normally drowned-out by the dominant

Mexican culture.

A sense of gratitude overwhelmed me. I

understood how the Seris once lived completely off the land with ease. They

thrived in their desert habitat because of their deep understanding of the

natural world and a strong tribal network of information exchange.

When a nomad walks off into the wilderness,

he knows where the resources are. He knows in what tree the mano y matate are hidden. Twenty miles away he has relatives or friends,

where he will stay the night and share information about his journey—what

plants he passed, the conditions of the land, what tracks he saw, and where the

best water sources were.

At the end of the Seri experience, many

questions remain unanswered. However, I knew one thing for sure: when you have

to walk a mile to reach fresh water or track an animal for ten miles before you

even get a glimpse of it, sooner or later you realize that in the nomad’s

world, it’s a long way from the sink to the refrigerator.