It’s 3:10 am and I wake by the bell loudly clanging in the hallway. The light switch is flipped on and the room full of men becomes alive. By the time I have rubbed my eyes, stretched on my futon and manage to get up, a full minute has passed. When I finally pull myself up to sitting position, I see my Japanese compatriots (I’m the only foreigner here), are not only up but somehow half of them have already pulled their sheets off and stowed their futon in the closet. By the time, I actually arise, most of them have finished this ritual after neatly folding the sheets and placing the quilts and buckwheat hull pillows in the closet. Although I believe I follow the zen admonition to get up right away at the bell, clearly these guys have better conditioning in this area. Oh, and no one is grousing about the early hour even though these are ordinary people who signed up for this three-day intensive at Eiheiji, the most important zen monastery in Japan, if not the world.

Thirty minutes later, I am in the zendo, wearing a grey yakuta with a black skirt, sitting on the zafu cushions facing the wall. After some initial rustling, the only sounds I hear are the slow intakes of air by my neighbor. Normally three bells ring to signal the beginning of zazen. However in the morning, we hear the heartbeat of the temple: the sounds of the huge taiko drum outside the hall slowly reverberate in and around the room, filling my body with its slow beat, telling me it is time now, time now to be still, time now to match my breath to the beat, time now to feel alive. The drumbeat is replaced by a series of bells and then back to the drum. When the silence returns it is somehow deeper as we have been transported to a deeper place in our own body. I forget it is early in the morning, I am awake in a timeless place.

Time passes, it is not my responsibility to see the clock. The taiko heartbeat returns with a new pattern, five beats and a roll down of beats. This is echoed by the bell with three beats and repeated by the han, a wooden block whose sound is deep but piercing. Another roll down signals those of us who have a rakusu or robe to put it upon our head as we chant the Robe Chant reminding us of our purpose and intent:

Dāi zāi ge dap-pu kū

Mu sō fu ku dēn-ne

Hi bu nyorāi kyō

Kō do sho shu jō

We repeat three times, take our rakusus or robes out of their cloth cases and put them on.

I turn in my seat to face the room, get up carefully, put on my slippers and turn back to plump my cushion. I bow to the cushion to thank it for supporting my practice, turn and bow towards the room, thanking all of the group (sangha) for supporting my practice. I join the line of practitioners and we leave the zendo one by one.

Back in our room, I have a short period to stretch, put on my white tabi (socks with a big toe to wear with sandals), and grab my chant book. At 4:30 am, I line up with the others and begin the long walk up and down stairways watching the passage of the centuries as we leave the new building with its air conditioning and go through the hallways in outdoor covered passageways hundreds of years old. Six of us lead the procession, carrying wooden covered buckets, some large and some small.

When we reach the Daikuin, the kitchen, the six of us enter this ancient building which has fed millions of monks and practitioners over it 650 year history. While the kitchen itself is modern, our entry is the same as one hundreds of years ago. We call out to the cooks that we are there and leave out vessels. We walk out and stand in front of the kitchen altar and bow in thanks for the food that will nourish us.

After bowing in groups of six, I continue my way with the others down the walkways, noticing the rain falling outside, the sounds of birds in the early morning and very sounds our feet make on the wooden floors.

We stop and bow in groups of six various times before we ascend the eighty or so steps up to the Hatto, the dharma hall, at the highest point in Eiheiji.

We leave our sandals on the top steps, each on a separate step and walk in our tabis into the Hatto. It is an immense hall that easily fits several hundred monks and visitors. We line up near the long outer open air entrance and sit in seiza, the Japanese kneeling sit. It is still quiet as we have arrived before the service is to begin. A dozen or so monks are busy with the tasks of light altars and making the arrangements for the ceremonies.

Slowly some senior monks come in. Their ranks are denoted by the color of their okesas (robes)–brown/golden for senior teachers,and black for monks. Each of the robes is a different of brown to gold, creating a beautiful mosaic of color and men. In addition there are slightly different designs of the robes while the yakuta underneath can be grey, black, deep blue or dark green.

Bells start ringing and different groups arrive and sit or stand in different places some pre-assigned. We continue to sit until we are summoned to stand up and again wait in silence. There is some noise of shuffling footsteps and from the left a hundred monks all with shaven heads walk in and are guided to their places in lines ahead of us. I hear more bells, this time higher in pitch which signal the advance of the head priest. To my surprise, as the entourage passes, I realize it is the 85-year-old Abbott of the temple, dressed in an orange robe with an elaborate embroidered okesa. He only leads special ceremonies and today apparently is one.

He leads the entire group in chanting and bowing. We sit, we stand, we sit and stand; we bow standing with our hands in gassho, together at nose height, we stand and bow with our hands clutched at our chest, we do full three prostrations from the standing position down to the floor with our hands reaching up. Despite the Abbott’s age, he still manages to the prostrations quickly, quicker than I can do them as my feet get caught in my skirt. We sit in seiza and sometimes bow part way down and later all the way down. This is all choreographed during different chants.

The chants themselves are invoking the Buddha in ourselves, whether it be of compassion or understanding. In my “English chant book”, the chants are written syllable by syllable in romaji so I can participate. The others have Japanese chant books usually composed with the Chinese characters which are also used in written Japanese. To my surprise, some of the chants I assumed to be Japanese were actually Japanese transliteration of Pali, a Sanskrit language used by Buddha when he was alive. It is the sounds that get carried forth, not necessarily the literal meaning.

We are invited to the altar one by one to offer incense. I feel myself walking with intent and strength in front of the all of the assembly. When I take a small amount of powdered incense and touch it to my forehead and add it to the burning charcoal, a small puff of smoke emerges and surrounds me. The smell and heat add additional sensory stimuli to my experience. I feel some great sadness well up and well as contentedness and fullness. Walking back, I feel joyful and determined.

The Abbott ends this part of the service of remembrance and compassion for the living. He walks out with bells announcing the ending of his participation. After some silence and moving around of items, the regular service begins. It has its own choreography, including the ritual distribution of the chant books to the monks. While most regular chants have been memorized, one in particular is in the Japanese/Chinese version of Pali and has its own book of about 60 pages. The monks are chanting syllables of words in a language they do not know. At first, we stand up while the hundred monks in front of us snake around the room in a fairly intricate pattern while they chant. The chant speeds up and then slows down, sometimes quiet and sometimes loud. Then it speeds up faster and faster, until I hear what sounds like a babble of sounds rather than a joint chant. They stop snaking around and stand in place while we were are motioned to sit down in seiza. I had the same chant book (in Chinese) and I attempt to follow by watching as others turn the pages. On the repetitious parts, I start to pick out the symbols and anticipate and even join in. It is an act of awareness to just follow along, my ears listening, my eyes trying to find the patterns in the book, my hands trying to hold the book correctly upright with my thumb and pinkie in the front and the other fingers in the back. My mind is fully occupied with this task. Nothing else matters in this moment.

We proceed through five other chants, a few familiar to me from my SF Zen Center practice. And then suddenly, it is completed. The bells indicate the recession and we turn to go back to the steps to put on our slippers.

We now walk back full of awareness of the new morning sounds, other bells and drums from distant parts of the complex mixed with the birds and footsteps. The six of us walk up into the kitchen to retrieve our food. We bow to the cooks in gratitude and line up, in my case holding a bucket of rice porridge straight ahead of me, one hand on each handle. As my sandal catches an edge on the first steps down, there is a gasp as I stumble forward. My skating reflexes are pretty good at keeping myself upright and I catch myself and make it down the steps okay. The thought crosses my mind, that we all are worried about tripping and falling and by my actually stumble, I might take some worry out of others. This is my gift to my group in the morning .

We follow the long hallways and stairways back to our area and deposit our food on a waiting table. It is now 6 am and I have been up for 3 hours already. In the short break that follows, I take off my tabi and then stepping with the left foot first into the zendo, I bow in recognition of all beings and walk silently to my cushion on the elevated platform. I bow to the pillow and to the group as before, flip my sandals off, scoot backward on my pillow, reach forward to store my sandals underneath, arrange my robes and twirl around on my pillow to face the wall again. I arrange my legs in a half lotus and the three bells start the period of meditation.

This is when it becomes difficult. My knees are already sore from the last hour and half of seiza and getting up and down. Finding the right level of support on the zafu is not easy. For my height and weight, I need about 6-8 inches of support to allow my knees and legs to be in the proper position. The soft pillows are much lower, so within 15 minutes my legs go numb and soon after the pain starts. I breathe into the pain, I focus on other parts of my body, I wiggle my legs, and spend a lot of time sitting with pain. My mind tells me, “Give up, move your legs.” I do this and it is of little avail. My mind responds with thoughts that the end of the session is near and that only makes the pain worse. Each breath feels more difficult. I now try focusing on counting my breaths and promise myself that when I get to ten and the bell has not yet rung, I will get up anyway. I reach ten and the bill does not ring. I force myself to begin counting over again. My mind keeps wondering. “Why isn’t the bell ringing? Did someone make a mistake?” And with each thought I become more aware of the pain. Finally I give up, am defeated and move my legs. Ten seconds pass and the bells rings and I become filled with my mind’s recriminations “You could have waited and held on for a short period longer. You are never going to finish this participate period. You are a failure.”

I did not know it but this mind game would be a constant for much of the day. This is why it is called practice.

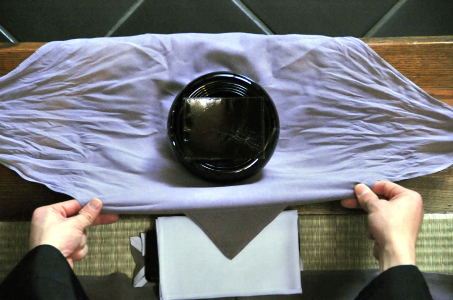

All meals are served in the zendo in oriyoki. Simply put we have a set of three bowls, chopsticks, a setsu (think of a spatula but instead it is a black lacquered stick with a square cheesecloth attached to the end) and three cloths, a small white one, a larger grey one and a medium blue one.

These items are all use in a relatively complex ritual of eating. There is a proscribed order of untying the cloths, arranging them on the wood edge of the tan before us and on our laps, arranging the bowls and putting out the utensils. Each action must be done with precise movements. Done correctly it is a beautiful mindful process of preparation to eat.

Source: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/eng/practice/food/oryoki/index.html

Source: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/eng/practice/food/oryoki/index.html

However, we are a room filled with 20 newcomers. Just opening our bowls and setting the utensils and cloths out, takes over 40 minutes, all the while sitting on a cushion in a half lotus position.

Source: https://terebess.hu/zen/szoto/oryoki.html

Source: https://terebess.hu/zen/szoto/oryoki.html

Serving is also done with precision. The meal is simple–rice porridge, pickled vegetables, and gomasio (ground up salted sesame seeds.) However, there are exacting movements to be learned to pick up the bowls (always with two hands), offering them to the server, receiving them back and placing them down. After a chant of gratitude for the food, we eat three quick bites of the porridge, and stop for another bow. Finally I get to eat, picking up the bowls with two hands (when I remember and/or reminded by one of the monks watching me), using a shoveling motion towards the mouth with the spoon, arranging the chopsticks in the same 10:20 clock position when I am not using them. Eating quickly without stopping.

When everyone is finished, we each clean out bowls with the setsu (of course, in the correct manner) and the servers come out with water (in the evening, they come out with tea then water both to clean the bowls.) We clean our bowls, inside and out, the chopsticks, spoon and finally the setsu and dry them in the exacting way with the white cloth. The monks come back to collect the rinse water. I carefully pour the bowl into the bucket with my right hand while guarding it from view and splashing with my left. I lift the bowl to my mouth to savor the few last drops. I then begin the process of arranging the bowls, eating utensils and cloth back together. First I grab the middle of the napkin cloth on my lap, with left hand on the top middle and right hand, underneath, pulling backward. I fold it in two and then in thirds and place it own the bowl. I place my eating utensils on top. I stretch my cleaning cloth along each edge, fold it half way across, flip it upside down to cover half of the bowls and then unfold it to reveal the portion with my name in the lower right hand corner. But it’s not in the right place indicating that I did it wrong. I repeat this again and again under the watchful eye of a monk. I finally unfold the cloth and my name is where it is supposed to be. I cheer quietly to myself. Another 30 minutes has passed. As beginners it takes almost two hours, with our teachers watching every move, gently correcting the movements and getting more particular about those movements the more proficient we get in the overall process.

My legs are aching and it is a relief to do the final chant, jump off the tan into my slippers (another thing I never quite accomplished, although to the Japanese participants, this was second nature), bow and walk out the zendo.

A thirty minute break is followed by soji, cleaning the zendo, and the bathrooms. Each of these has specific tools to use and a manner in which to do them. I brush off the tatami mats we sit on in the zendo with a broom. I sweep the floors and wash the floors with a wet rage bending over from the waist with two hands on the rage moving it from side to side down the long walkways in the zendo. My heart beat raises with the effort and the workout feels good.

I brush my teeth and wash my face before I go back to the zendo for 40 minutes of sitting, followed by walking meditation, and 30 more minutes of sitting. It is now 11:00 am and I have been up for 7 hours . We begin to prepare for lunch, This time oriyoki only takes one and half hours. The pain in my legs remind me of each minute and that this is not something I do regularly especially in the half-lotus position. My mind wants me to scream and tells me, “This is not what you signed up for.”

The afternoon schedule contains an hour dharma talk by one of the teachers, for which we are soon sitting in seiza at small desks. For the Japanese, this is a relaxing position. For me, sitting on my ankles for an hour is another way of torturing a different part of my legs.

When it is over, we have a ten minute tea break before we return to the zendo for another two sessions of zazen.

Oriyoki again at 5:30 pm We are getting better and we manage it in 45 minutes. My legs are still sore and aching. However relief is ahead. We have 30 minutes to go to the o-sento in basement to clean up. We walk down the steps in two rows and when we get to the o-sento, we bow. We take off our clothed in the out-room and then enter the spa room itself. I sit on a small white plastic stool in one of the cleaning stations and with a hand spray fully wash and clean myself. After, I am thoroughly clean, I join my compatriots in the soaking tub which is about 110 degrees F. It feels good to stretch my legs and I massage them in the hot steaming water. I stay as long as I can before I get out, rinse myself off with cool water and dress again.

I am back seated in the zendo at 7:10 pm. Two more sessions of zazen, separated by walking meditation. Now I feel warm, light and no longer have pain in my legs. My mind which has been in hyper-drive, relaxes as I stare at the wall. For this time period, I am not counting the minutes and when the bell rings am surprised how quickly time passed.

The last chant of the evening is called Fuganzazengi and is in Japanese It is a chant I do not know but by this second evening, I feel myself being carried forward, my voice more confident with the phrasing, fully engaged in the power and beauty of our chorus of voices.

Tazunuru ni sore, dō moto enzū,ikade ka shushō o

karan, shūjō jizai nanzo kufū o tsuiyasan. Iwan ya, zentai

haruka ni jinnai o izu, tare ka hosshiki no shudan o shin

zen. Ōyoso, tōjo o hanarezu, ani shugyō no kyakutō o

mochiuru mono naran ya. Shikare domo, gōri mo sa

areba, tenchi haruka ni hedatari, ijun wazuka ni okoreba,

funnen toshite shin o shissu. Tatoi,e ni hokori,go ni

yutaka ni shite, betchi no chitsū o e, dō o e,shin o

akiramete, shōten no shiiki o koshi,nittō no henryō ni

shōyō su to iedomo, hotondo shusshin no katsuro o

kikessu.

Iwanya, kano gion no shōchi taru, tanza roku nen no

shōseki mitsu beshi,shōrin no snin in o tsutauru,

menpeki kusai no shōmyō nao kikoyu. Koshō sude ni

shikari,konjin nanzo ben zezaru…

It continues on to the last verses.

Sude ni ninshin no kiyō o e tari, munashiku kōin o wataru

koto nakare. Butsudō no yōki o honin su, tare ka midari

ni sekka o tanoshiman. Shika nomi narazu, gyōshitsu wa

sōro no gotoku, unmei wa denkō ni ni tari. Shukkotsu

toshite sunawachi kūji, shuyu ni sunawachi shissu.

Koi negawaku wa, sore sangaku no kōru, hisashiku mozo

ni naratte, shinryū o ayashimu koto nakare. Jikishi

tanteki no dō ni shōjin shi, zetsu gaku mu i no hito o

sonki shi, butsu butsu no bodai ni gattō shi, soso no

zanmai o tekishi seyo. Hisashiku inmo nam koto o

nasaba, subekaraku kore inmo naru beshi, hōzō

onozukara hirakete juyō nyoi naran.

Later I discover the the name–Song of Zazen, Fukan zazengi 普勧坐禅儀

(Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen)

The last two stanzas stand out for me.

You have gained the pivotal opportunity of human form.

Do not pass your days and nights in vain. You are taking

care of the essential activity of the buddha-way. Who

would take wasteful delight in the spark from a flintstone?

Besides, form and substance are like the dew on the

grass, the fortunes of life like a dart of lightning – emptied

in an instant, vanished in a flash.

Please, honored followers of Zen, long accustomed to

groping for the elephant, do not doubt the true dragon.

Devote your energies to the way of direct pointing at the

real. Revere the one who has gone beyond learning and

is free from effort. Accord with the enlightenment of all

the buddhas; succeed to the samadhi of all the ancestors.

Continue to live in such a way, and you will be such a

person. The treasure store will open of itself, and you

may enjoy it freely

It’s 9 pm and I have been up for 18 hours. I brush my teeth, roll out the futon and bedding and dive into bed. I will be awake again in 6 hours.